Hemlock Society

[Vaguely spoiler-y. Also, if suicide is a trigger topic for you, I can imagine this film may come off as blasé, simplistic, or even offensive.]

I've spent a lot of time trying to understand the path of popular, mainstream Bengali movies from the Suchitra-Uttam films of the 50s to today's remakes of Telugu masala, and I wonder if Hemlock Society and its ilk—less loud and macho than the Telugu remakes, not as heavily message-driven as art films—are the most faithful descendants. The name alone indicates that this film is About an Important Aspect of the Human Condition, but it's also funny, dynamic, and at moments very sweet. Director-writer Srijit Mukherji is responsible for a few of these kinds of films; I've seen the interesting but imperfect Autograph and the maybe-good-on-paper-but-actually-eye-roll-y Baishe Srabon.*

Hemlock Society quickly develops a sense of an increasingly bizarre and slightly dream-like subculture, full of kooky minor characters, within the "real" world it first establishes. It pushes this new weirdnesses to some interesting extremes with humor that keeps the overall feeling a little off-kilter, neither as dark nor as saccharine as I thought it might become. The film acknowledges suicide as a complicated issue and in doing so creates characters who spend a lot of energy processing thoughts and emotions. Doubt and confusion are central to many of these people.

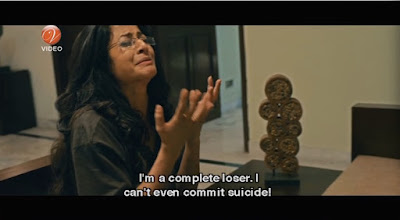

Meghna (Koel Mallick, whom I know only from countless song sequences from the afore-mentioned Telugu remakes and who has the most enviable ocean of dark, wavy, shampoo-commercial-worthy hair) is dumped by her terrible fiancé and instantly turns to attempts at suicide (we later find out her relationship with her dad and stepmom is strained and that she's having a hard time at work, too), only to be interrupted by Ananda (Parambrata Chatterjee), who barges into her apartment under the pretense of looking for terrorists.

Ananda is clearly a loon—practically a Manic Pixie Dream Boy, though the flip in gender in that dynamic instantly makes it somewhat less annoying, as do his breezy attitude and humor. Not the least of his quirks is constantly referencing Hindi films, an unusual trait for a Bengali film character in my experience. But he tells Meghna what she wants to hear, affirming that suicide is a rational response to an upset life. He then shares that he works with a secret organization that teaches people how to actually make it through the misrepresented and complex process of killing themselves effectively. She allows him to take her to the Society's training facility, which sits on the same grounds as Ananda's film studio (he inherited a lot of money and has indulged in various projects). At the end of the film, it becomes clear that there's a connection of ideals between the two campuses, but most of the time the proximity of the dream factory just reminds us how unrealistic the Hemlock Society seems.

I've spent a lot of time trying to understand the path of popular, mainstream Bengali movies from the Suchitra-Uttam films of the 50s to today's remakes of Telugu masala, and I wonder if Hemlock Society and its ilk—less loud and macho than the Telugu remakes, not as heavily message-driven as art films—are the most faithful descendants. The name alone indicates that this film is About an Important Aspect of the Human Condition, but it's also funny, dynamic, and at moments very sweet. Director-writer Srijit Mukherji is responsible for a few of these kinds of films; I've seen the interesting but imperfect Autograph and the maybe-good-on-paper-but-actually-eye-roll-y Baishe Srabon.*

Hemlock Society quickly develops a sense of an increasingly bizarre and slightly dream-like subculture, full of kooky minor characters, within the "real" world it first establishes. It pushes this new weirdnesses to some interesting extremes with humor that keeps the overall feeling a little off-kilter, neither as dark nor as saccharine as I thought it might become. The film acknowledges suicide as a complicated issue and in doing so creates characters who spend a lot of energy processing thoughts and emotions. Doubt and confusion are central to many of these people.

Meghna (Koel Mallick, whom I know only from countless song sequences from the afore-mentioned Telugu remakes and who has the most enviable ocean of dark, wavy, shampoo-commercial-worthy hair) is dumped by her terrible fiancé and instantly turns to attempts at suicide (we later find out her relationship with her dad and stepmom is strained and that she's having a hard time at work, too), only to be interrupted by Ananda (Parambrata Chatterjee), who barges into her apartment under the pretense of looking for terrorists.

Ananda is clearly a loon—practically a Manic Pixie Dream Boy, though the flip in gender in that dynamic instantly makes it somewhat less annoying, as do his breezy attitude and humor. Not the least of his quirks is constantly referencing Hindi films, an unusual trait for a Bengali film character in my experience. But he tells Meghna what she wants to hear, affirming that suicide is a rational response to an upset life. He then shares that he works with a secret organization that teaches people how to actually make it through the misrepresented and complex process of killing themselves effectively. She allows him to take her to the Society's training facility, which sits on the same grounds as Ananda's film studio (he inherited a lot of money and has indulged in various projects). At the end of the film, it becomes clear that there's a connection of ideals between the two campuses, but most of the time the proximity of the dream factory just reminds us how unrealistic the Hemlock Society seems.

|

| The film studio also provides a reason for a cameo by Bengali action hero Jeet, a frequent co-star of Koel Mallick. |

If you are a more alert viewer than I am, or even just a bigger fan of Rajesh Khanna movies, you might realize that a very upbeat, fillum-obsessed character named Anand(a) who helps the droopy and despondent probably means that this film is not actually saying that suicide is a good idea. I have not seen Anand, but from what I read there are indeed some commonalities with that film. I won't go into them, but let's just say that I was uncertain what direction Hemlock Society was going to take and to what purpose for much longer than I should have been.

I'm actually glad I didn't figure out the film earlier because wondering what exactly was going on is a pleasing experience. I love black comedies, and this film inhabits that territory much more often than most Indian films I've seen. The training facilities of the Hemlock Society are my favorite part of this strangeness. There's a main hall, a mix of sterile white and almost church-like architecture except for large portraits of famous suicides (you can see Kurt Cobain on the right);

classrooms dedicated to instruction in different methods of killing yourself, each garishly saturated and filled with imagery of that technique;

and an interrogation room filled with scribbles and letters (presumably suicide notes, from the few I could read), presided over by a priest in a chair that is half umpire, half lifeguard.

I'm actually glad I didn't figure out the film earlier because wondering what exactly was going on is a pleasing experience. I love black comedies, and this film inhabits that territory much more often than most Indian films I've seen. The training facilities of the Hemlock Society are my favorite part of this strangeness. There's a main hall, a mix of sterile white and almost church-like architecture except for large portraits of famous suicides (you can see Kurt Cobain on the right);

classrooms dedicated to instruction in different methods of killing yourself, each garishly saturated and filled with imagery of that technique;

|

| Throwing yourself in front of a train cannot work in India, he says: the trains are often late and the rescue crew will reach you before the train does. |

The symbolism in the visuals is heavy, but the dialogue is funny and the film never seems earnest about it. Furthermore, Meghna herself is clearly disoriented by all of this and can't quite figure out what to make of it either. The sense of "is this for real?!?" is amplified by the appearance of big-name Bengali actors who appear as faculty. Barun Chanda (probably best known for Ray's Seemabaddha and also familiar to current Hindi film audiences from Lootera and Roy) teaches about trains (pictured above), Sabyasachi Chakraborty explains how to effectively slit your wrists, complete with dummy arms that gush blood, and Soumitra Chatterjee plays an army colonel who demands Meghna come up with a better reason for killing herself than just a stupid boyfriend, suggesting political protest or selflessly risking her life in a patriotic act of war.

In retrospect, Hemlock Society's principal message is unsurprising. Instead, the pleasure in the film is how it rolls out that message, combining funny but uncomfortable extremes with largely uncommented-upon pity for humanity's many shades of suffering. Despite the weirdness and Ananda's savior complex, it's a human-scale story, with ordinary people trying, failing, learning, and then trying again. It shows the ability of strangers to intervene to positive effect, the importance of reaching out to those who suffer, and the necessity of taking time to stop and think before committing life-altering acts—all handled with straightforwardness and humor. The film also provides this wonderfully hyper-self-aware Bengali-film dialogue (I think in parody, though I could also be convinced it's in earnest), for which I am eternally grateful, as Ananda tells Meghna about his ideal woman:

And I thought Hindi film heroines were unrealistic.

And I thought Hindi film heroines were unrealistic.

* I have every intention of also watching Mishawr Rawhoshyo because HELLO it seems to involve Egyptian archaeology.

|

| This professor debunks a method used in Bemisaal. |

Even though they're not playing themselves, their presence adds gravitas to the strands of thought that swirl through Meghna's head as she struggles to figure out her honest responses to what her life has become. They do what good teachers are supposed to do: lead her to questioning what she thinks she understands and inspire her to keep digging. Dipankar Dey plays Meghna's father, a doctor, who is slow to realize the seriousness of his daughter's condition but does what he can to protect her, including giving the ex a pretty fantastic public shaming (and, more importantly, learning to listen to her). Rupa Ganguly is a calm, deep presence as Meghna's stepmom, quietly doing a better, if thankless, job at parenting a grown daughter than Meghna's biological father.

* I have every intention of also watching Mishawr Rawhoshyo because HELLO it seems to involve Egyptian archaeology.

Comments